Original replica of the first phonograph.

Photo credit 1.

Phonograph recording on tinfoil.

Photo credit 5.

Click here to see a close-up showing the sound impressions.

|

Whether you are a newcomer or old-hand to old-old-time sounds, you'll enjoy this voyage into the wonderful sounds of the early twentieth century.

Overview of Contents |

Please note:

|

From the earliest phonographs in 1877, courtesy of Mr. Thomas Edison, the cylinder was the preferred geometric form for a record. The first records were strips of tinfoil, the predecessor to household aluminum foil, wrapped around a 4-inch diameter drum. The drum was hand-cranked at about 60 revolutions per minute (RPM) and the phonographic apparatus made sound impressions upon the foil. The expected lifetime of a foil recording was short, because after a few playbacks the foil would often rip.

Original replica of the first phonograph. Photo credit 1. |

Phonograph recording on tinfoil. Photo credit 5. Click here to see a close-up showing the sound impressions. |

| Return to the top |

By 1888, a cylinder record standard had emerged; it was made of wax and had shrunk in size to a little over 2" in diameter and 4" long -- and it was brittle. Recording at a standard 100 grooves per inch, early wax cylinder recording speeds varied -- slower speeds like 90 RPM for spoken material would yield a 4 minute recording, faster speeds from 120 to 160 RPM for music would run for about 2 minutes. Within a few years, phonographs were being sold for the home market and by 1902 the recording speeds were standardized to 160 RPM.

Edison 'Home' model B phonograph, 1906. Photo credit 5. |

Close-up of Edison 'Home' phonograph playing an old wax record. Photo credit 5. |

By late 1908, 160 RPM 4-minute wax cylinder records became available. The groove density was doubled from 100 to 200 per inch, thus the playing time doubled (see note 1). Columbia records got out of the cylinder record business in favor of disk records in 1909. Victor records never sold cylinder records, preferring the disk format. Edison continued making two-minute cylinders until late 1912. Edison finally stopped making all entertainment records, cylinders and disk, in October 1929 -- one day before the stock market crash.

| Return to the top |

Edison music room, Orange, New Jersey laboratory, 1890-93. Photo credit 1. Click here to see a close-up (see note 2). |

Edison music room, Orange, New Jersey laboratory, 1905. Photo credit 1. |

Due to the inflexibility of the recording diaphragm, some instruments did

not record well. Instruments producing complex sounds, such as the violin,

recorded weakly. Not surprisingly, horned instruments recorded best.

Consequently, marching band numbers were prominent in many early recordings.

To produce a clear recording, the number of instruments would also be

kept to a minimum -- 15 or so for a band, 4 or so for a chorus.

Therefore, many early recordings present a simpler music by necessity.

Today, recording and disseminating sounds is direct and simple. Spare a thought for how far things have come: With no method for mass-producing copies of a single recording, early inventories of recordings were created by huddling multiple phonographs near the performers. Each phonograph would be operated simultaneously, each making a recording of the performance, the recorded cylinders would then be replaced with fresh blanks, and the process repeated.

|

The music of the United States Marine Band, of Washington, D.C., is now so well known to the users of the phonograph and the patrons of coin-slot machines, that The Phonogram, desiring to give its readers precisely what they want, irrespective of cost, has procured, after considerable effort and expense, the fine photograph of that band while it is making records for the Columbia Phonograph Company. The photograph shows the band in full uniform, as it appears when playing for the President of the United States at the White House, on state occasions, or in the grounds of the White House in pleasant weather.

Photo credit 2. See note 3. Click here to see a close-up. This is, in many respects, the most celebrated band in the world. It can play, without notes, more than five hundred different selections. Much of the music played by this band to the phonograph has been arranged especially by the band with a view to the best phonograph effects; and the patient experimenting of Professor Bianchi, who is in charge of the musical department of the Columbia Phonograph Company, has borne fruit in an output of superior records. With regard to musical records, it may be here stated that anyone possessing an ordinary knowledge of the phonograph can make them, but perfect records are only obtained by using the utmost care and precision in placing the horns and by the perfect running of the phonograph. |

Soon, primitive duplicating methods were devised by connecting one phonograph to another. An early approach used a hollow rubber tube running from the master phonograph to the recording phonograph. Later, direct linkage connected the reproducing stylus of the master to the recording stylus of the other phonograph thus duplicating pantographically. Only a limited number of copies could be made using these techniques due to degradation of the original recording. By mid-1902, cylinders could be copied by a molding process. This was a big improvement and cylinder prices dropped. At the same time, the wax itself was changed from a soft brown wax, which limited the playback lifetime of recordings, to a firmer black metallic soap-wax concoction.

Many two-minute cylinder recordings were self-announcing. This was a standard practice due largely to the lack of labelling on the early wax cylinder records, and also because, silly as it may sound, there was no reason not to self-announce the selections. By 1904, Edison began labelling his cylinders on their edge, and by 1909 most Edison records were generally no longer self-announcing.

| Return to the top |

Light brown wax. |

Medium brown wax. |

Darker brown wax. |

Dark grey wax; early molded cylinder. |

Black wax; labelled molded cylinder. |

Edison carton & cylinder, 1899. Close-up of the carton's left face; right face. |

Edison carton & molded, unlabelled cylinder, 1904. |

Edison carton & molded, labelled cylinder, 1908. |

Columbia cylinder cartons Columbia records were sold through Sears-Roebuck under the name Oxford. Close-up of an 1898 Columbia carton's front face; left face; right face. |

Columbia wax cylinder |

| Return to the top |

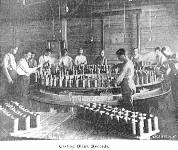

| Casting Blank Records |

|

| Turning the Blanks |

| Making Band Records See note 4. |

|

| Making Violin Solo Records See note 5. |

| Testing the Records |

|

| Testing the Phonographs |

| Return to the top |

|

|

|

Compiled and edited by Glenn Sage

Enjoy an hour of two-minute wax cylinder phonograph music recorded on high-quality cassette tape. Although wax cylinders were originally recorded acoustically, they have been reproduced here directly from the original cylinders using an electronic means that captures all the available sound (see note 10).

|

| Return to the top |

| Return to the top |

| Return to the top |

| Return to the top |

| Return to the top |

|

Installed: August 31, 1996. Last updated: September 11, 1996. |

Courtesy: http://www.digits.com |